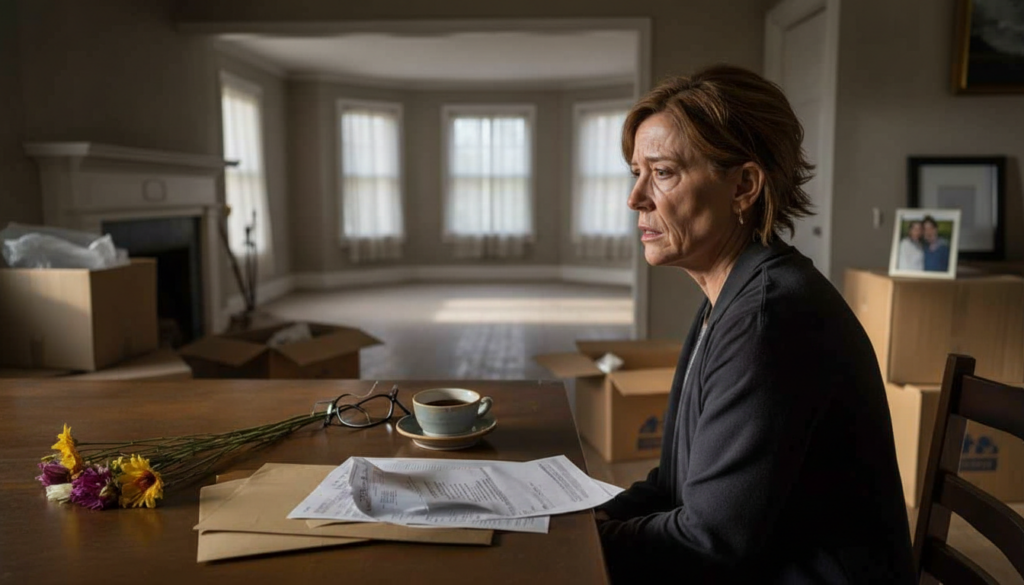

The day after the funeral, the house didn’t sound right. It was too quiet, like it was holding its breath. Anna went into the kitchen, expecting to hear the kettle whistle like it used to when her husband forgot it on the stove. There were flowers, half-finished casseroles from neighbours, and an open brown envelope on the table that she was too scared to touch. It came from the IRS.

She had to read the words three times before they made sense. “Tax on inheritance due.” For free. About the house they had built together. On the bricks that still smelt like him. Her hands began to shake.

“Why is the state charging me for love if it’s priceless?” she whispered into the quiet of the tiles.

At that point, sadness changed into something else.

No one tells you about the second blow. People often use soft words to talk about widowhood, like “loss,” “absence,” and “moving on.” No one talks about the letter with the official stamp that comes like a second accident. One day you’re picking out a coffin, and the next you’re learning about tax brackets and allowances.

The house you walked back to after the funeral isn’t just a safe place anymore. It is an asset that can be taxed. A line on a form. A number that might or might not go over a limit set by people who have never been in your living room and looked at an empty armchair.

Maria, who is 52 years old, lost her husband in a car accident on a rainy Tuesday. They didn’t have any kids, just a small flat in a city that was growing. Prices had gone through the roof in the last ten years. When she met the notary, he quickly figured out the current market value, then subtracted any debts and the tax-free allowance for a surviving spouse in her country.

He smiled and said, “Good news: you only have to pay taxes on part of the value.” Good news! She left the office with a bill that was almost equal to a year’s worth of pay. A year of mourning turned into a year of looking for money. She got rid of her car. Her small collection of jewellery. She let a stranger rent the second bedroom.

There is a cold mechanism behind these individual shocks. The state looks at everything that the dead person owned, like their house, savings, life insurance (if they had it), and sometimes even their car. Then it takes away what the law says a spouse or child can get without paying taxes. The tax rate that applies to the rest of the money depends on the country, the relationship, and the amount.

The big silent problem is real estate. Values slowly go up every year, but salaries barely move. A house that felt “normal” to the couple when they bought it can suddenly be above the tax line. The widow doesn’t feel any richer. In writing, she is. In writing, grief can be “worth” six figures.

What you can do when the taxman comes to your door of grief

The first thing you want to do is put the letter in a drawer and never look at it again. That’s how people are. That’s self-defence. The better move is to go slower and more gently: you get a pen, a calm friend, and you start writing down what you see. House. Loan. Saving. Insurance. Debts.

Then you ask a specific question: “What are my options besides ‘pay or lose the house’?” In a lot of places, you can pay in installments, get a partial exemption for your main residence, or have your payment delayed. Some widows don’t hear about them because they stop paying the first bill. The system doesn’t often explain itself well. You have to pull the thread until you can see the whole picture.

The most common trap is to hurry. Selling the house for a low price just to “get rid of the problem.” Signing whatever the notary tells you to because “they know how this works.” Let’s be honest: no one really reads every line of every document in those first few weeks. Your mind is cloudy. Your sleep isn’t good.

One simple rule that can save lives and roofs is that you shouldn’t make big decisions alone. You bring a brother or sister, an adult child, or a close friend who isn’t going through the same grief as you. You ask the awkward questions, like, “What if I can’t pay all at once?” “Can I stay here and pay over time?” “Are there any exceptions for low-income people or spouses?”

Elise, 61, says, “They told me I could either sell my house or borrow money to keep it.” “Nobody told me I could spread the tax over several years.” I only learned that from a support group for widows, not from an official source.

Get a full breakdown of the inheritance tax, including how much comes from the house and how much comes from other assets.

- Find out if your country gives surviving spouses money, lets them keep their main home tax-free, or lowers the tax rates for low-income heirs.

- If you have to sell the house right away to pay the full amount, ask for staged payments in writing.

- Get in touch with a notary or legal aid clinic that doesn’t make money from selling the property.

- Keep all of the tax office’s letters and emails, along with the dates, so you can challenge mistakes or ask for more time.

When grief and money come together, something in us breaks down.

There is a simple tension at the heart of this story: we value love, but we value homes. The same living room can be a place where you remember things at 8 a.m. and a taxable square metre number at 10 a.m. when the assessor calls. Many widows are mad, ashamed, or both because of that crash.

Some people will say, “That’s the law, and everyone knows it.” But when death suddenly comes into your life, you don’t have time to prepare with spreadsheets and legal advice. There is only a knock, a siren, or a phone call in the middle of the night. Then there was the paperwork.

We’ve all been there: when a bureaucratic demand comes up in the middle of a personal disaster and you feel like the system doesn’t see you.

That could be the beginning of a new conversation about the inheritance tax on the family home. Who should be protected first: the budget of the state or the person who just lost their partner and needs a roof over their head? How many years of shared life does a widow have to “pay back” before love stops being a taxable event? These are things you should say out loud, not just mumble over an envelope at the kitchen table.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| — | Understand that the family home can trigger inheritance tax, especially in rising property markets | Helps you anticipate a potential tax bill before being blindsided by an official letter |

| — | Explore payment plans, exemptions, and spouse allowances instead of rushing to sell | Gives you room to breathe, keep your home longer, and avoid panic decisions during grief |

| — | Bring a trusted person and ask blunt questions to notaries and tax offices | Reduces the risk of signing away rights or missing support options just because you’re overwhelmed |

Questions and Answers:

Question 1: Is it possible for a widow to be forced to sell her home to pay inheritance tax?

Yes, in some cases. If the total value of the estate is high and there isn’t enough cash or other liquid assets to pay the tax, the house may be the only way to do so. Depending on the laws of the country, payment plans, loans, or exemptions for a primary residence can sometimes help you avoid this.

Question 2: Do all countries tax the surviving spouse on the family home?

No. Some countries give spouses very high allowances or full exemptions, while others tax them over a certain amount. The rules are very different from place to place, so it’s important to get local advice from a notary or tax expert.

Question 3What if my partner dies and the house is still under mortgage?

Usually, the value of the property is lowered by the amount of the outstanding mortgage before the inheritance tax is figured out. That could lower or even get rid of the amount you owe taxes on, but it also means you might have to keep paying the mortgage or talk to the bank about lowering it.

Question 4: If I can’t pay everything at once, can I work something out with the tax office?

Yes, a lot of the time. When paying right away would be very hard, many tax authorities will let you set up an installment plan, extend the deadline, or, in rare cases, forgive part of the debt. In most cases, you have to ask for this in writing and show proof of your situation.

Question 5: Is there anything couples can do to keep the surviving partner safe before one of them dies suddenly?

In some legal systems, they can look into things like specific marital property regimes, life insurance set aside for taxes, co-ownership structures, or early donations. These decisions are both technical and personal, so it’s best to get help from a professional while both partners are still alive and calm.